Vern Visick, Pandomaniac

We are moving toward a joyful event – a road trip to the Pando grove in south-central Utah. For those of us who have been involved with Pando for some time, this trip is tinged with sadness. One person, especially, should be with us, even among those leading us. Vern Visick. We lost him to illness in an untimely way. Yet we feel that he is with us. Certainly, we remember.

Vern Visick was a man always doing what good he could. This was never the blind striking out sometimes associated with the “do-gooder,” when that term is used pejoratively. His decisions about what to do were thoughtful and well-informed. His PhD was in social ethics, and his years of study and reflection guided him. For several decades he worked in Madison, Wisconsin. He found that his most effective ways to do good were through conferences. Years ago, he invited me, the eco-economist Herman Daly, and Sen. Gaylord Nelson for a conference on economics. He saw some importance in the book that Herman and I had written, called “For the Common Good.” We were grateful for the recognition and exposure, and we can trace some significant consequences to the conference he organized for us.

In Madison, he created an annual lecture series in Lent that became the Lenten programs for many of the churches. In Claremont, the Episcopal priest John Forney worked with him to create a similar program that we call “Agenda for a Prophetic Faith.” It continues and is another part of Vern’s rich legacy.

Four or five years ago, some of us wanted to bring Bill McKibben to Claremont and build a program around him. Vern joined the planning group. Soon we all learned that we had in our midst a master organizer on whom we could rely.

I had been thinking of organizing a much larger event around McKibben on the occasion of the tenth International Whitehead Conference, focused on ideas and practice associated with the philosopher Alfred North Whitehead. But I was not sure that I could handle my ambitious dreams. After I had seen Vern in action, I asked if he would work with me. He was not a card-carrying Whiteheadian, but he saw a possibility for doing good; so he agreed. Thanks to his gifts and dedication, we made a success of a very complex plan.

The “Seizing an Alternative” conference was planned to lay foundations for future action. Some of us created an organization to build on the conference. Vern contributed to getting it organized and established with 501(c)3 status. Initially we were sure only of having a lot of good material to preserve and share, but we were open to respond to opportunities, and these arose.

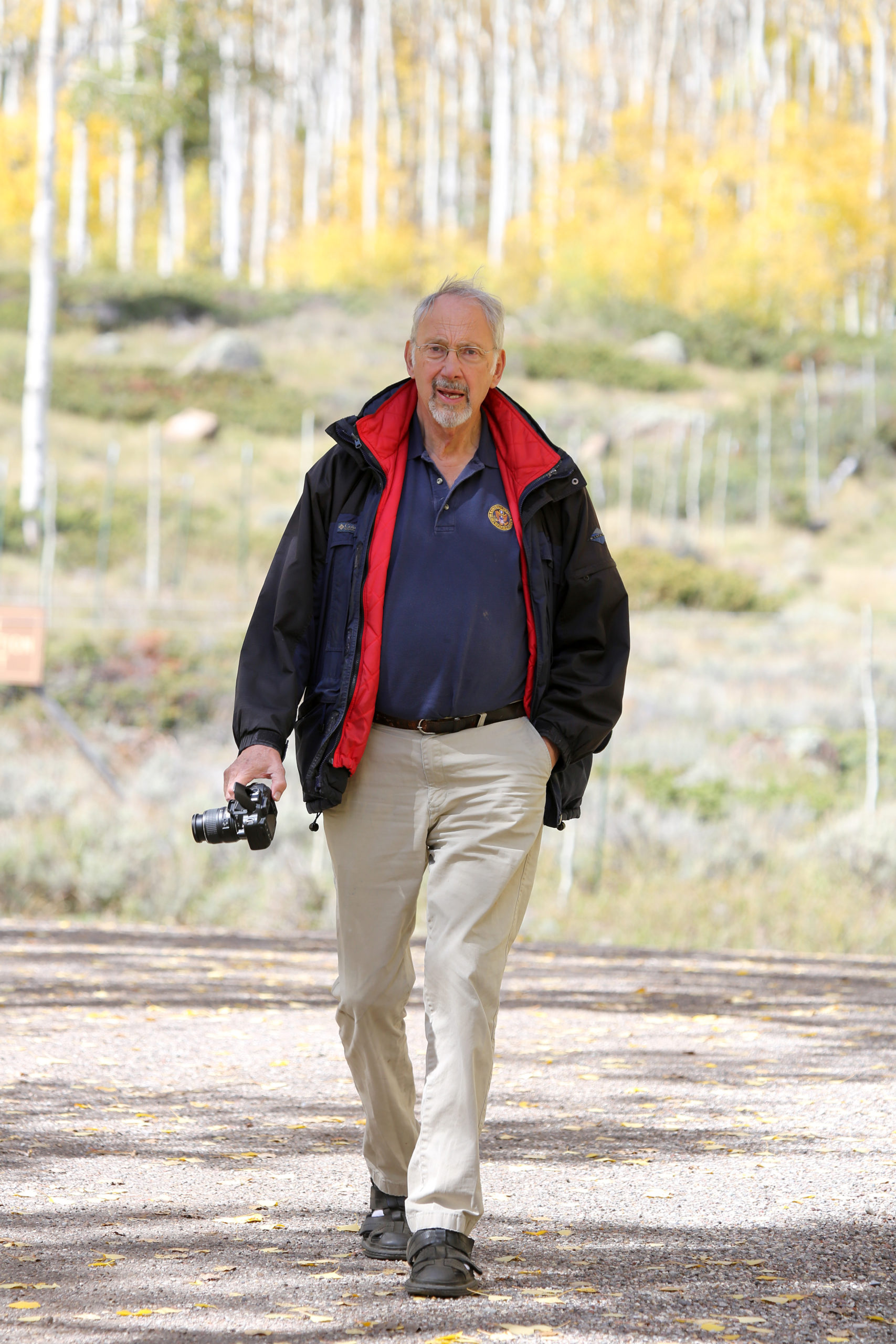

The new organization needed a name, and Vern took part in a meeting to settle on one. He was involved in the group that came up with “Pando Populus,” the name that was chosen. For him, this was more than a name. He was the first among us to go to see the aspen grove and, with a friend and collaborator, Bob Ireland, take beautiful photographs and video. He understood that connecting to Pando by name gave us another chance to do good. And he urged us to recognize the good we were called to do.

The Pando grove, which is the world’s largest organism and surely one of its oldest, is threatened by human action. We humans had killed all the wolves in the area, and the deer population exploded. They have eaten everything that could be eaten. That included many infant trees produced by the one root system. New shoots are needed to keep the system alive. As we took Pando’s name, Vern urged us to commit ourselves to saving it. The Roadtrip to Pando is an expression of his commitments.

We have several organizations growing out of the Whiteheadian community’s commitment to a philosophy of ecological relations. Their goals are ultimately all the same – what I would describe as contributing to an ecological civilization. A small group of us has met once a week to brainstorm about the goal, about how each of the organizations fits in, and about how they can support one another – as well as about new challenges and opportunities. Vern was a faithful participant and a wise counselor. When he took an assignment from the group, no one doubted that it would be well executed.

For decades in Madison, he was very much his own man. It was his ideas that he implemented. I have been blessed by knowing others who have worked very hard and effectively to do good for the world by implementing good ideas of their own. But Vern was not limited to that. He was willing to work just as hard to implement the ideas and programs of others – if he judged that under the circumstances they had the best chance of doing good.

Vern and I had both attended the University of Chicago. We had both studied with faculty who introduced us to the work of Whitehead. We had both studied also with the truly remarkable philosopher Richard McKeon, the neo-Aristotelian. Although I took more classes with him than any other professor, and certainly recognized his genius, his thinking never grabbed me. I never felt that I fully understood. Over time, I more and more fully gravitated to Whitehead’s vision. The programs to which I have referred grew out of that vision.

Vern, on the other hand, understood McKeon profoundly and found that, at a deep level, McKeon’s approach to philosophy gave him the perspective he needed. He identified himself as a “neo-Aristotelian.” Nevertheless, when he found that in Claremont it was the Whiteheadian vision that had been established and was proving fruitful, he set his personal preferences aside, and threw himself into support. This willingness to work hard to fit into someone else’s program because, under the circumstances, it offered the best chance to do good, expresses a rare and beautiful spirit. You will understand that I feel a special gratitude.

In this cynical age, one may wonder what drove Vern to a life of vigorous, thoughtful, and often stressful, service. Many people discount such answers as love of God and neighbor, or concern for the future of humanity. Psychologists are expected to dig up something from childhood that explains one’s need to win adulation or please authority figures, or overcome a deep sense of unworthiness. I do not doubt that all of us can be explained, with some truth, in these ways. But there is also some truth in the idea that some of us really do care what happens to other people, to humanity as a whole, and even to the whole biosphere. I personally have no doubt that Vern cared.

Vern was a Christian believer, which means that he also loved God. Already in the New Testament it is clear that love of God and love of creatures are inseparable. Because we love God, we love all that God loves, and that is everything. We cannot live without destroying some others, but we can do so gratefully and gracefully and mindfully. We can certainly seek to limit this destruction and maximize the constructive and supportive, the creative and the healing, relationships.

Those who care and find ways to serve are free from one problem that besets so many. For them life has meaning. What happens matters, and the possibility of helping to shape what happens, even a little, matters. Of course, there are times of deep discouragement, sometimes, perhaps, despair. But even that is part of a life filled with meaning.

Those who find meaning in service, day by day, rarely think about what death will bring. If death is simply the end, that does not invalidate the meaning of having brought joy to one child. But many who love God, and experience God’s love as well, expect that there will be more. They are sure that this “more” will not be torment for our sins. They believe that God always gives us what joy the circumstances allow and we accept. We may refuse that joy after death as we have so often refused it in this life. We may isolate ourselves and make ourselves miserable then as now. But God will call us then, as God calls us now, to be open to joy – to enjoy it.

When I think of one, like Vern, who has worked so much more to bring good to others than to acquire it for himself, I feel joy in imagining that he experiences joy in feeling the gratitude of so many he has helped. But I do not doubt that there is work to do, there as well, and that Vern is busy doing it. The “eternal rest” of which some speak would, I suspect, be hard for Vern to take.