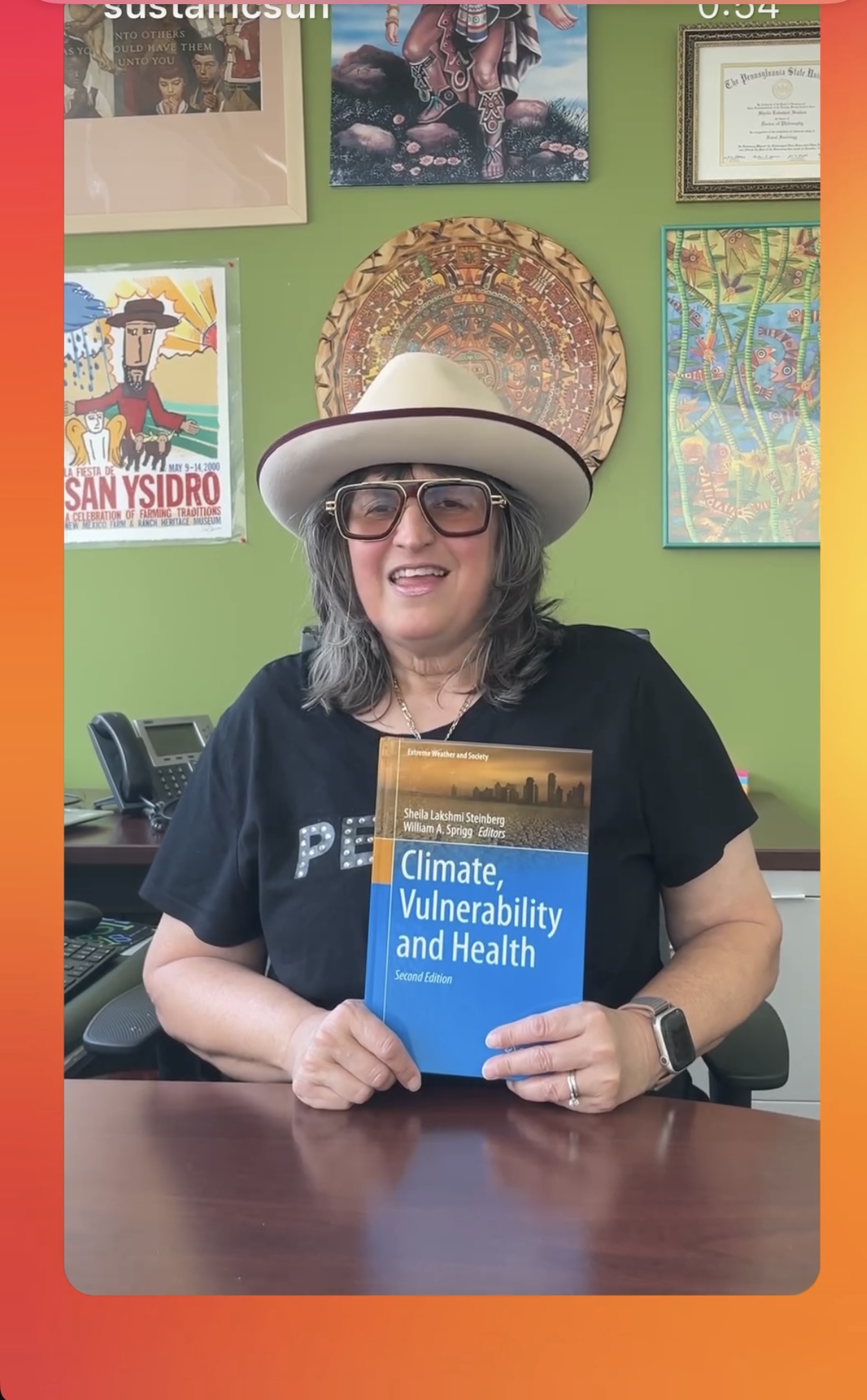

Climate, Vulnerability and Health: An interview with Sheila Steinberg

Dr. Sheila Lakshmi Steinberg has a new book out, Climate, Vulnerability and Health, which we’ve been eager to hear all about. Professor Steinberg is team lead for an ambitious Pando Days project and is Director of the California State University Northridge (CSUN) Institute of Sustainability.

PANDO: Professor Steinberg, thanks for being here. We loved seeing your CSUN project develop over the prior Pando Days season. I think there were a total of four CSUN projects over the last season, and they all had such imagination and urgency. We’re eager to hear more at the Pando Awards at Caltech, Oct. 5.

But now – we get to turn the spotlight on you and your new book, Climate, Vulnerability and Health.

PROFESSOR STEINBERG: Thank you. Working with the students on these projects really energizes me. They’re not waiting for someone else to solve climate challenges—they’re jumping in, and that spirit of collaboration runs right through the book as well.

Tell us about your book. What’s at the heart of it?

It’s a volume I co-edited with William Sprigg as part of a larger series, Extreme Weather and Society, with Springer Nature Link as series editor. It highlights how both climate change and the COVID-19 pandemic have exposed and intensified environmental inequalities and social disparities.

We pulled together voices from geography, climate science, public health, sociology, and engineering to ask one big question: How does climate change shape people’s daily lives?

It’s not just about rising temperatures or stronger storms—it’s about who breathes the smoke, who loses their home, who has resources to recover and who doesn’t. So it’s part scholarship, part lived testimony.

That makes it sound like vulnerability itself is being redefined in broader, more interconnected ways.

Yes. Vulnerability isn’t only “being in harm’s way.” It’s about the uneven scaffolding of society—who has infrastructure, political power, and resources when disaster strikes. A fire in one neighborhood means inconvenience; in another, it leaves scars that last for generations. That social architecture is as important as the climate event itself.

For you as a scholar, is it difficult to hold the rigor of science and the weight of human experience at the same time?

They don’t actually pull apart. Science gives us tools and data; lived stories give those numbers meaning. In the book we have, for example, a filmmaker documenting the Maui fires through survivor testimony, and an engineer analyzing the aftermath of the Paradise fire. Together they create a richer, more human truth.

So storytelling isn’t just illustration—it’s part of how we know.

Exactly. Stories help communities make sense of what data alone can’t capture, while data grounds those stories so they don’t evaporate after the news cycle. When the two come together, the research becomes both credible and deeply relatable.

What’s next for you and this work?

Books are important, but they sit on shelves. The real energy comes when people gather—screenings, dialogues, workshops where artists and scientists meet community members.

One idea we’re excited about is a public showing of Healing Lahaina, a documentary on the Maui fires by Laurel Tamayo, who also wrote the foreword to the book. A film like that doesn’t just inform—it invites people to feel, to connect, to act. And pairing it with discussion opens up room for collaboration and resilience-building.

You’re making the case for climate scholarship that refuses to stay walled off.

Absolutely. The ivory tower doesn’t have a fire escape. If scholarship isn’t porous—if it doesn’t move between campus and community—it misses the point. These crises are too urgent for silos. We need science, art, and community wisdom leaning on each other.

Any last thoughts?

Just this: climate change is no longer out there somewhere—it’s here, it’s personal, and it’s reshaping how we live. The fires in Los Angeles make that plain.

Addressing vulnerability isn’t optional; it’s a collective project. And if we can approach it with creativity as well as rigor, then we’re not only responding to disaster—we’re imagining futures worth living.

Thank you so much for your time — and your valuable work.