Shoji’s Memories, and Mine

The New Yorker has published Shoji’s memories of the trauma of the first atomic bomb. She wrote as one of its surviving victims. My memories are very different. I was shaving in the army barracks at Camp Ritchie, Maryland, when I heard the news. The shock left me shaky and feverish for several days. It brought back memories from fifteen years earlier.

As a boy of four, with my brother, six, I liked to play with a neighbor’s dog, which was chained on a short leash. The neighbor did not mind, except that in our love for the dog, several times we had released it from the chain, joyfully sharing its joy in freedom. My vivid memory is of how I felt when the voice of the invisible neighbor requested, quite gently, that we not release the dog. Suddenly I recognized that the deed that seemed so right and joyful when I considered only me and the dog was far from innocent when viewed in a larger context. What swept over me may have been partly fear, but I think it was mostly guilt. I ran home and never visited the dog again.

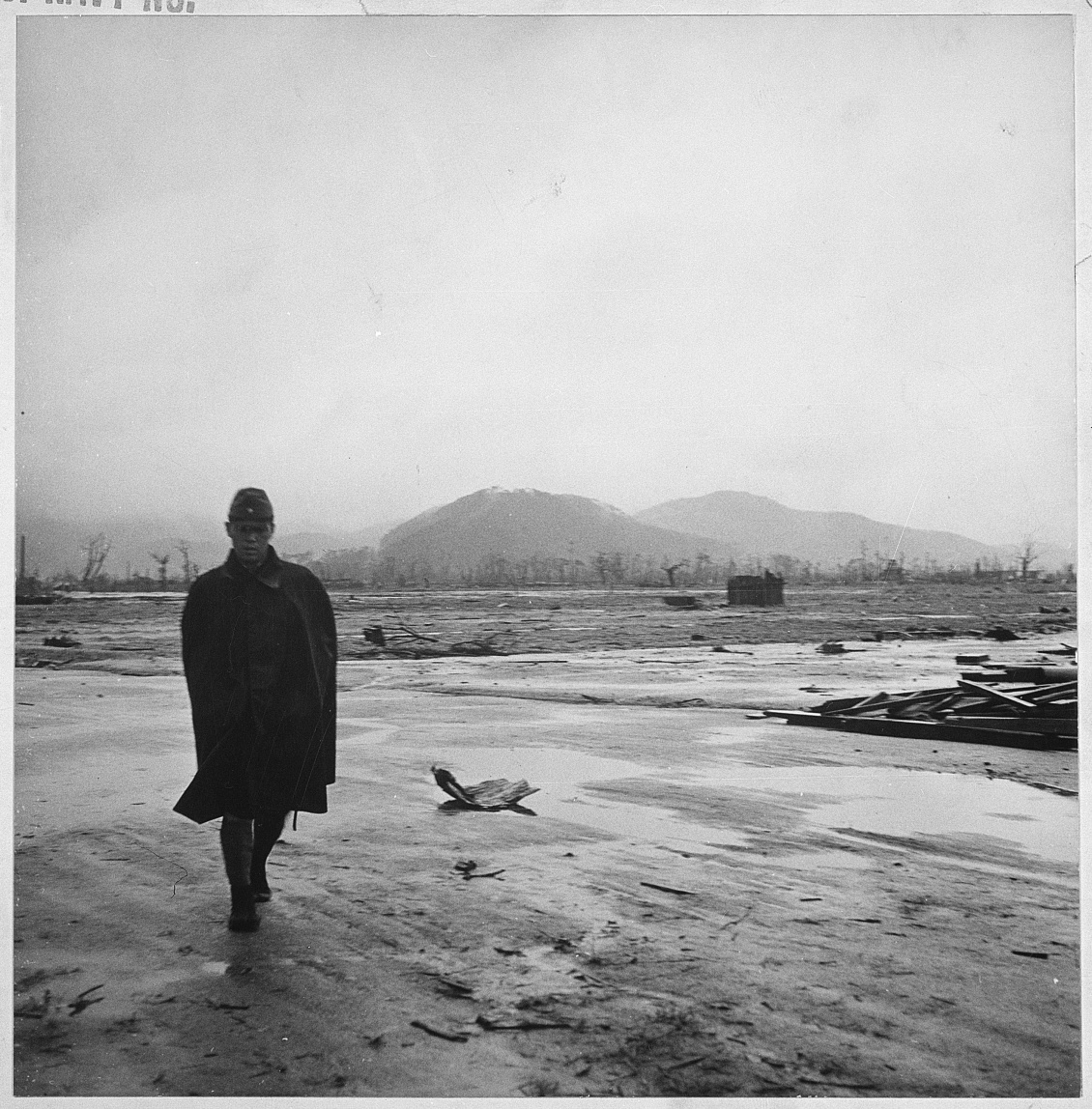

Now between these two events one connection was just that of deep feeling. But that feeling was heightened by the fact that the city that had been obliterated by a single bomb was the city in which I had played with the dog: Hiroshima, my childhood home. Later I was to learn that perhaps the most active survivor was Rev. Tanimoto, a Methodist preacher, a friend of my Methodist missionary parents. I think they had helped arrange for his studies at Emory University.

There is another connection between the two events. I learned at four that what seems in itself good may be very wrong in a wider context. I hope that this lesson has inhibited the rush to judgment. The dropping of the bomb was in itself a terrible evil. Was it justified in a wider context, for example by its shortening the war? Did the end justify the means?

I, like many others, have gone back and forth on this question. I do believe that good ends can sometimes justify bad means. But I have also come to the conclusion that this is far rarer than the opposite situation in which bad results outweigh the achievement of some short-term good. The consequences of evil means seem to proliferate rather than be contained by the good end that is first thought to justify them. Once we have opened Pandora’s box, we have foreclosed many opportunities for good that existed before that act.

For me, personally, the consequences were good. The war ended. I was in Japan with the army of occupation. The people accepted us kindly, almost welcoming us, so relieved that we were not raping and pillaging. McArthur governed well. I got out of the army without ever being close to combat and had a GI bill to complete my education.

Without the bomb there might have been a costly American invasion of Japan. As a Japanese-language officer, I might have been attached to a unit involved in the invasion and gradual conquest. The destruction of Japan might have been greater than was the case. I might, of course, not have survived.

My judgment that the use of the bomb was wrong is not an easy one.