Strong Sustainability

We’re all familiar with the concept of sustainability. But did you know that there’s a debate regarding whether sustainability strategies should be “weak” or “strong”?

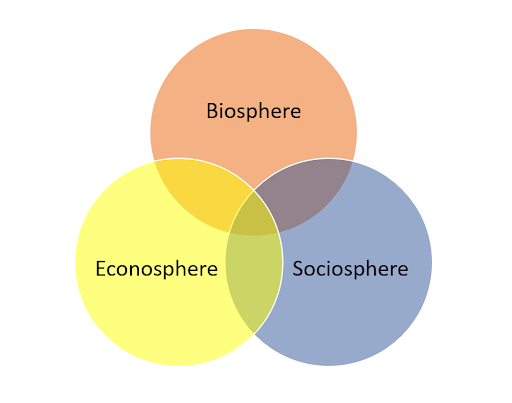

The easiest way to grasp the difference between “weak sustainability” and “strong sustainability” is by comparing two different diagrams illustrating each position. Both make use of the common observation that sustainability needs to include three dimensions: environmental, social, and economic. But the way in which they imagine the relationships among those dimensions differs.

Preliminary observation: The distinction between “weak” and “strong” sustainability seems to have been crafted by the “strong” folks. Nobody wants to admit that they are approaching sustainability in a weak way.

But indeed, there are key differences between the two basic approaches. One diagram, admittedly the most commonly-accepted, presents a Venn diagram of three sometimes overlapping circles: environmental, social, and economic.

Sustainability occurs where all three overlap together. This is a view that the “strong” folks identify as “weak.” Why is that?

According to advocates of strong sustainability, the flaw in the diagram of overlapping circles is its implication that while sustainability is good, it isn’t a precondition to the functioning of any of the three systems it portrays. In particular, the Venn diagram seems to suggest that unsustainable economic and social systems can endure, even if they are not as satisfying as they would be if they intersected with one another and with healthy environmental systems.

Proponents of strong sustainability take issue with the idea that social and economic systems can endure at all without a sustainable environment. They furthermore are alarmed at the assumption by many mainstream economists that substitutes can always be procured for economic products that society deems valuable, so we need not worry about exhausting any specific kind of natural or human resource.

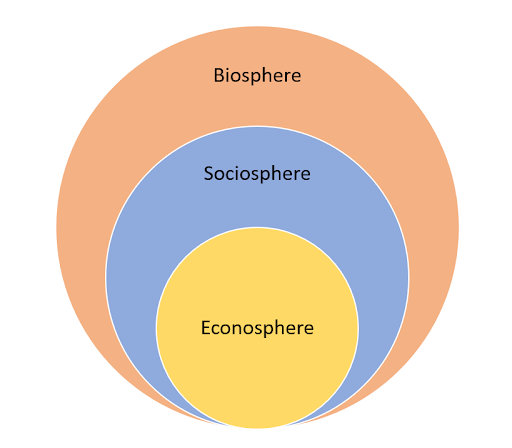

Instead, the strong sustainability folks argue that social and economic systems are necessarily nested within environmental systems which provide enormous, albeit often unacknowledged, benefits to society and the economy. These benefits are so great that a healthy society and economy cannot long endure without a healthy environment. So their alternate diagram contains three nested circles: environment is the all-encompassing large circle, society is somewhat smaller, and economy is contained within both society and the environment.

The strong sustainability diagram appears much less frequently than the weak sustainability diagram, but it does have some influential supporters. Most notably, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency relies on the strong sustainability diagram to support its perspective that emphasizes environmental protection as fundamental to sustainability.

And I’ve come to value especially the perspective of an organization called Ecosystems United that substitutes the terms biosphere, sociosphere, and econosphere for the more common terms environment, society, and economy in most sustainability diagrams and concepts. By prioritizing the biosphere we are reminded that this all-encompassing dimension of sustainability permeates all life forms, humans included, not just the “external” environment.

Here, then, is how the Ecosystems United folks characterize the two versions of sustainability:

What is meant by “strong sustainability”?

Weak Sustainability

Strong Sustainability

How did I come to this perspective, and what implications does it have about the way I think about sustainability planning in the Los Angeles area? In 2016, I retired from a 13-year stint as the regional planning director for the Metropolitan Council of the seven-county Minneapolis-Saint Paul Metropolitan Area in Minnesota. Since the 1960s, Minnesota law has supported an unusually robust approach to planning for that region.

The Metropolitan Council does more than planning. While it plans for regional transportation, it also owns and operates the regional transit system. And while it plans for water resources in the region, it also owns and operates the regional wastewater system. Moreover, it sets policy and provides funding for a 55,000-acre regional parks and trail system.

And perhaps most remarkably in a nation that largely defers to local government for ultimate land use decisions, the Metropolitan Council requires that the 181 cities and townships in the region update their local comprehensive plans every ten years in a way that conforms to the regional systems that it manages.

Ten years ago, I was working with my staff to update our newest regional plan, a plan that we called Thrive MSP 2040. One of the issues we wrestled with was how to deal with sustainability. We concluded that sustainability was not just a good idea that could be added onto a plan that dealt with many other issues as well.

Instead, it must be a feature of all good regional and local planning. So, we identified it as the final outcome of everything that we aspired to accomplish in our region, whether we were dealing with natural systems (the biosphere), social systems (the sociosphere), or the economic systems (the econosphere).

Although Los Angeles’ approach to regional planning is considerably different from that of the Minneapolis-Saint Paul Area where I still live, I believe that the “strong sustainability” perspective aligns well with what I see in the collection of plans that I have become familiar with and analyzed in my e-book, Sustainability Planning in Metropolitan Los Angeles. I want to say a bit about what I’m seeing in L.A. within the dimension of natural systems. I’ll be writing more about this topic in future blogs, but here is a high-level overview of my thoughts on this subject.

I believe that there are three bedrocks to a healthy, regional approach to natural systems planning in our day. First, there must be vigorous efforts to reduce greenhouse gas emissions dramatically, by changing both the ways we produce energy and how we consume it. My next blog post will look especially at the new regional transportation plan and sustainable communities strategy that has been crafted by the Southern California Association of Governments (SCAG) to be adopted in early 2024.

The SCAG plan will contain goals and strategies to reduce carbon footprint stemming from transportation and land use planning. Second, increasingly severe drought and flood cycles are making it necessary to engage in better ways to manage water in the Los Angeles region. We will examine how regional water agencies and other levels of government are reimagining their mission via a “One Water” lens that integrates all forms of water management (surface water, groundwater, drinking water, industrial and agricultural water, wastewater) along with land use planning.

Finally, we’ll consider the remarkable biodiversity index that has been created by the City of Los Angeles for areas within and adjacent to the city limits. Arguably, healthy biodiversity is the ultimate environmental goal of sustainability planning, so the importance of this index is great. Later blogs will then examine how robust natural systems must then be tailored to support what Martin Luther King called the “Beloved Community,” including social and economic systems that advance the common good as well as individual well-being.

We’ll start this consideration with a look at the Los Angeles County OurCounty sustainability plan that in many ways serves as a bridge between hyper-local and hyper-regional perspectives, while addressing all three levels of sustainability – natural systems, social systems, and economic systems.

I look forward to sharing these thoughts and engaging in conversations that may be inspired by them.