The Man in the Moon

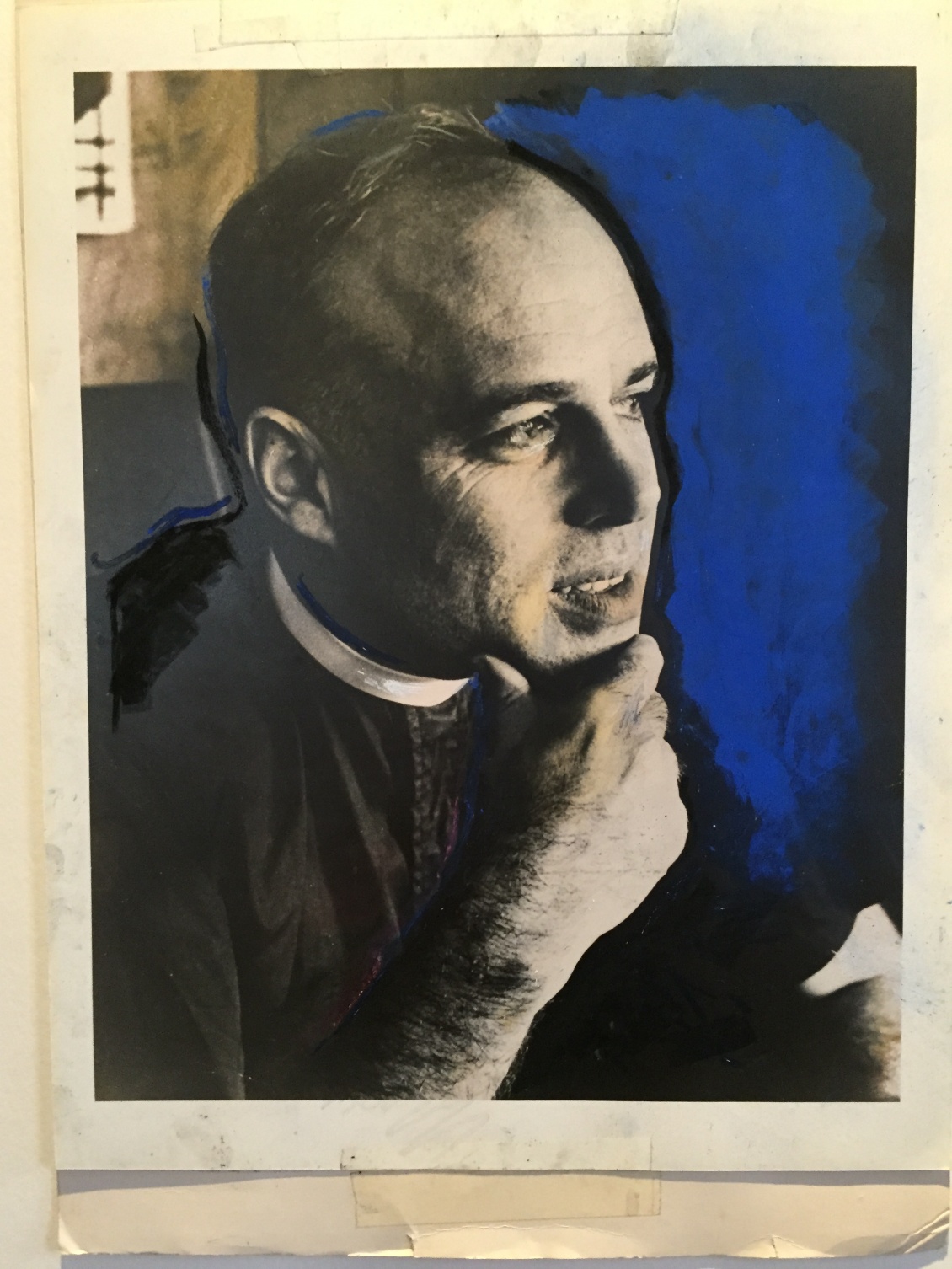

Malcolm Boyd died this past Friday, February 27, in Los Angeles, having been sent on his way by friends and friends-turned-family. He was the last surviving link to silent film legend Mary Pickford, anti-war and social activist (he held a peace mass at the Pentagon and marched with King), gay Episcopal priest and Canon, poet (Time Magazine called him the Shakespeare of prayer), and stirrer-up of all sorts of trouble. He was 91 and a half.

Malcolm, of course, was best known for the million-plus best-seller, ARE YOU RUNNING WITH ME, JESUS?, a small book of poems/prayers that spoke of a God deeply embodied in the world at a time when that was shocking in the way it was put. One of his 1965 prayers began along the lines of, “I’m in a gay bar, Jesus.”

Malcolm and me

I first met Malcolm in the early 1980s when I read an opinion piece he wrote for the Los Angeles Times that identified him as a priest and gay, with a background in Hollywood. I had been studying philosophy of religion at Claremont Graduate School, had just embarked on my first documentary film (human rights, in the U.S.S.R.), and was in the process of coming out to myself as gay. I wrote to Malcolm hoping for a response from a like-souled elder — which I got, and we became long-time friends. More than anything else, we shared the same sense of humor. I could laugh with Malcolm in ways I’ve been able to laugh with not many others.

Malcolm gave me the first (and only) erotic novels I ever had — thumbed-through but not the sort of thing one would likely read cover-to-cover. I had been raised as a Seventh-day Adventist in Oklahoma. For me, sexuality was something I had stomped on. For a young gay man trying to discover his own sexual identity, these were beautiful books — all the more so because the man who gave them to me was a priest who was interested in connecting me with the energies of my life and bringing about some healing.

As the years rolled on and I went in and out of love many times, I would tell all to Malcolm and to Mark Thompson (his husband) — in letters if I were traveling, or across one of our dinner tables — and in the process connected to some of the deepest parts of myself. Malcolm was famously great friends with Playboy founder Hugh Hefner (Hefner said not many years ago that Malcolm was the person who knew him best). It’s a relationship that probably still puzzles some. But at times I’ve been able to imagine that I pretty well understand the connection.

The only time I’ve ever done mushrooms was with Malcolm. It was extraordinarily intense — so much so that while I would, in a way, love to do them again, I’ve never sought them out because the original experience was so satisfying, all that time ago. This was years back on a bright Saturday afternoon in the Silver Lake neighborhood of Los Angeles. I still remember in great detail the places I visited throughout the universe that day.

In one experience, I went through a door, suspended among stars, and entered a room. Inside was a dragon, which I instinctively thought to fight. I was genuinely scared, and began putting on some traditional-looking armor to prepare for a battle. As I was getting dressed, I heard a voice from somewhere saying, “Why do you want to fight the dragon? It will make such a bloody mess all over the floor. Why not play with it?” And so I took off the armor and the dragon and I started to play. It played rough, but I came through the romp OK. When I’d had enough I flew off through the space I was in and on through another door and into another experience.

I had thought the drug’s effects would be relatively short-lived. I had a conference to attend the next day in Claremont, with John Cobb, David Griffin, Frederick Ferré and other philosophers from the Whitehead camp about a project we were collaborating on and I wanted to feel up to the task.

In fact, however, I didn’t feel as able as I wished (I felt like I’d been playing with a dragon!) and couldn’t help but mention it over lunch to Ferré . I said something like, “My apologies, Frederick, if I’m not seeming very coherent — I just did mushrooms for the first time yesterday and didn’t think the effect would linger.” Frederick had been putting food on his plate from a buffet line when he stopped and said, “My goodness, tell me all about your mushroom experience and I’ll tell you all about my experiences with LSD at Harvard.”

Frederick is now gone, as is Malcolm. But my mushroom experience, whatever the content, opened me to the fact that there is a dimension to reality that my normal senses just don’t pick up. And while experiences like this certainly don’t prove anything about life after death, they do sketch out a landscape where an afterlife would not be the least bit unusual. I think lots of people, whether through drugs or not, have had experiences of one sort or another that suggest the same thing. When I think about Malcolm now dead, I find some comfort in this, even if I wouldn’t know where to go looking to find him.

The man in the moon

I took Malcolm to Claremont some years ago to meet John Cobb at the retirement community where John lives, Pilgrim Place. John, always generous and gracious, invited us for lunch at the dining hall; John’s wife, Jean, joined us at the table.

At some point over lunch, Jean said something about the man in the moon (I forget the context). John added that he had never been able to see the man in the moon. Malcolm responded that he had always been in love with the man in the moon.

And at that moment I realized why I had always loved Malcolm and John both as much as I have — because I know exactly what John was talking about (I’ve never quite been able to discern a face in the moon, either), but the moon has always and totally had the ability to sweep me away. I puzzle over big ideas even as I am a romantic at heart.

I told Malcolm not too long ago about our upcoming “Seizing an Alternative” conference but it didn’t quite interest him. Maybe it was my pitch, or maybe it was just the evening. His response took me a bit off-guard, because his entire life had been all about seizing alternatives, questioning assumptions, and poking taboos. And I know he believed the planet is committing suicide.

Maybe he was just too tired to keep pressing against the tide. But in retrospect I doubt that the fight in him ever left.

I think it was nothing more than simply the fact that he was just not very philosophically inclined. I never engaged him much in any discussion about the philosophy of Jesus. He was just interested in running with him.

I think, however, that Malcolm would have enjoyed the conference more than he thought; he would have fit right in. There is a track exploring gender and sexuality. A section devoted to reenvisioning religion in the direction of world loyalty as opposed to world escape. A group delving into matters of war and peace. A rethinking of culture for an ecological civilization. And even a track exploring the sorts of parapsychological experiences and dream-like states that he and I knew that day, years ago, on the lawn.

The philosopher Alfred North Whitehead once wrote, “Speak out in acts; the time for words has passed, and only deeds will suffice.” Malcolm was Whiteheadian in this sense, just in the extreme (he was all about extremes). His only question throughout the greater part of his life was, “Are you running with me, Jesus?”

Beyond the run, however, there is the peace. This is the peace, they say, that passeth all of our understandings.

May peace be with you, Malcolm.