The “One Water” revolution and sustainability

In April of 2016, at the national conference of the American Planning Association, I learned about a new way of thinking and acting that was creating a revolution in the water management business. Appropriately held in water-starved Phoenix, this conference included an afternoon workshop on something called “One Water,” an approach with profound implications for sustainability planning that originated with water professionals and was beginning to influence the field of city and regional planning.

The easiest way to understand One Water is to contrast it to traditional ways of managing water. Traditionally, various uses of water were managed separately. There were separate agencies and professions for managers of stormwater, wastewater, water in natural systems, water for irrigation, and drinking water. Each had their own set of goals and projects which often had little to do with one another. Angelenos are vividly aware of that approach every time they contemplate the Los Angeles River. Stormwater managers had been given the assignment of assuring that the city was safe from river flooding. Their solution was to turn much of the course of the river into a concrete, open-air storm sewer that channeled rain water quickly out to sea.

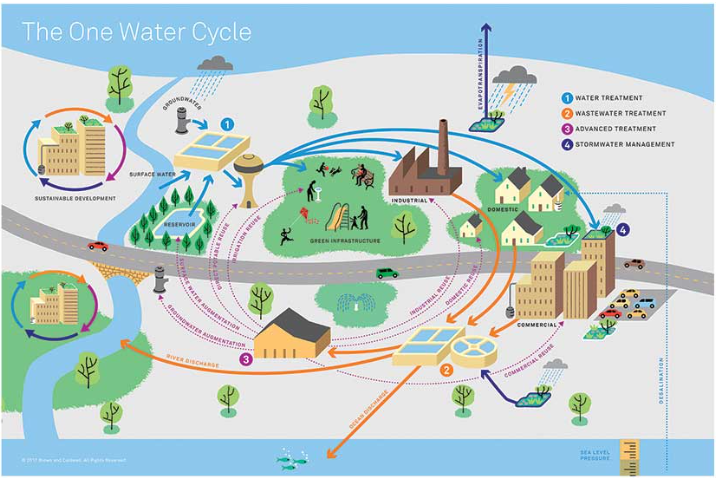

As its name suggests, the One Water approach proposed the radical idea that all water should be managed as a single system with different aspects that can create opportunities for fruitful integration. So, for example, storm water should not be just jettisoned into the ocean, but should be managed in a way that could capture water for drinking purposes and/or contribute to healthy plant and animal communities along the shores of a natural stream rather than just an open storm sewer. Treated wastewater should be considered as a potential source of drinking water. And so on…

Here’s an interesting exercise to illustrate two paradoxical realities – that the general public has probably never heard of One Water and that the One Water revolution is well underway among water managers and sustainability planners. First, try searching on “One Water” as a book title on Amazon. I came up with exactly one result, a story of adventure in the Alaskan wilderness. Then try Googling on the term “one water.” When I did so, Google told me that there were “about 13,180,000,000 results.” Admittedly, not all of the thirteen billion results were about the water management revolution I’ve described, but many were. The reference listed first in my Google search is actually a great place to start learning more about One Water as I’ve described it. Take a look at this from the US Water Alliance: https://uswateralliance.org/about-us/vision-for-a-one-water-future/.

So, how does the One Water revolution get considered in the new edition of the CSO Task Force e-book Sustainability Planning in Metropolitan Los Angeles: Products and Processes that I authored? First, I want you to think about the cover for this book. The design is intended to evoke both fire and water, the two fundamental dimensions of the natural world that need to be in a “Goldilocks” relationship for long-term sustainability to be achieved. (Not too hot, not too cold; not too wet, not too dry.)

A moment’s reflection will confirm that the focus of most recent sustainability planning has been on the “not too hot” dimension of the world. We’ve been urgently trying to prevent catastrophic global warming by reducing greenhouse gas emissions.

When greenhouse gas reduction is the focus of sustainability planning, however, there isn’t necessarily a concentration on the equally vital “not too wet, not too dry” dimension of things. That’s why sustainability planning in most metropolitan areas must consider a number of different planning efforts, not just one. In our e-book, we look at thirteen of them to see how different plans from different agencies provide a more complete picture of plans, strategies, and actions needed to achieve the complete hot/cold wet/dry balance that can yield long-term sustainability.

Thanks to the survey of thirteen different plans in our e-book, we can see that at all levels of government in Metropolitan Los Angeles, water agencies have bought into the One Water paradigm. This is true for the Metropolitan Water District’s Regional Reliability Outlook, for Los Angeles County’s Integrated Regional Water Management Plan, and for the City of Los Angeles’ One Water LA 2040 Plan, all of which are described in the e-book.

So, water management strategies in the Los Angeles region are being integrated with one another. But are they also being integrated with greenhouse gas reduction strategies? The answer to this question is also, happily, “YES.” And necessarily so! Returning to my account of the One Water workshop I attended in Phoenix in 2016, I vividly recall how the presenters introduced their talk. They were all water managers and they confessed to be doubly nervous about their presentation. First, they were nervous about being on stage with other water managers whose careers had previously focused on just one aspect of water management. They were still learning about what other kinds of water managers did and how they could better cooperate with one another. But second, they were even more nervous about the necessary work that they were learning to do with people in the city and regional planning profession. In their new world of One Water, they were now needing to consider how their water systems could relate effectively to transportation and land use systems which they had largely ignored in the past and are the responsibility of city and regional planners.

This is the kind of collaboration and integration that is also being embraced within Metropolitan Los Angeles by the various agencies working on different aspects of sustainability. The task is complicated and difficult and cannot be achieved overnight. And, yet it could not be more urgent. There is an ancient Latin phrase that is appropriate for integrated sustainability planning: festina lente (make haste slowly). We must move ahead both quickly and deliberatively to achieve our overall goal of deep sustainability, balancing as best we can the needs of natural systems (not too hot, not too cold; not too wet, not too dry), social systems, and economic systems. Metropolitan Los Angeles has a good start to doing so in a way that can inspire this vital task elsewhere in the United States and throughout the world.