To hear and to see: Interview with John Cobb

We try to sit down with Pando’s founding Chair John Cobb as often as we can to talk about the big ideas related to creating a more sustainable world. This conversation, held over Zoom and edited for clarity and length, focuses on sight and hearing and the different views of reality each gives rise to.

John Cobb has been called the most significant philosophical theologian of our time and is the leading authority on the philosopher Alfred North Whitehead. He is a member of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences.

Pando: John, I’ve always wanted to have a philosophical conversation with you about the senses, so here’s my chance! You have said some especially interesting things in the past about hearing and sight, in particular, and how they give more shape to our assumptions about the world than we typically realize. Let’s launch in.

John Cobb: Because Western culture is such a sight oriented culture, I would like to begin with a historical point. When we go back in history 2,500 years, we find people even then in India who affirmed both Atman and Brahma. Atman is the substantial self and Brahma is being itself. And of course, the relationship between Atman and Brahma and so forth is all part of the discussion which arises out of the sight orientation.

One thinker, Gautama…

Whom today we think of as “Buddha.”

He came to the conclusion that there is no Atman and there is no Brahma.

Let me make sure this is clear. The Buddha was saying, there is no “substantial self” or “I” or “me” that underlies my experience. And there is no “being itself” that is at the root of everything around us. He was going against what seemed to be common sense in India at the time.

The history is very interesting that, having rejected the implications of a sight-oriented culture, as India was and still is, he never had any significant influence in India. But, when his ideas came to China, and then also to Japan, Korea, and some other places, they were accepted without any problem. And that’s because they spoke a language which did not feature sight the same way that Indo-European languages do.

Fascinating. But talk a bit more about that. How exactly do Indo-European languages feature sight so predominantly?

In the Indo European languages, the sentence revolves around the subject.

And the subject is often what you can actually see.

We use a noun or a pronoun for the subject most of the time. If you just take typical sentence formations which have been the basis of our formulation, of logic, and so forth and so on, they begin with the dog, or the mountain, or something. So, the sentence seems to be about something.

Some thing. An actual thing of some sort. A substance.

And something can have other true sentences constructed about it.

The thing that is “substantial” finds itself in this circumstance or that, but it remains the same over time while events or circumstances are happening to it.

I was sick yesterday. I expect to talk to so-and-so this afternoon. I am now talking to you. I’m looking out the window and seeing trees. The language suggests that the word I refers to the same thing in all of those uses.

And the language, therefore, does not suggest that the I is exhaustively or necessarily identified as one who is seeing green out of the window, or as one who has particular plans for tomorrow, or is one who was sick yesterday or whatever.

Those things are incidental to the self – the I. “I” am more fundamental, more “substantial” than that. Or so we think.

So, when we ask what the I is, we have to say that the I is something that is present in or underlies all of the activities and characteristics in all of the sentences about the I. It underlies, but does not include all these characteristics.

If I’m seeing a patch of green color out the window, or am sick or whatnot, the self is the “substance” in this case.

It’s something that stands under…The “I” mentioned above is identical despite changing circumstance and characteristics; that is, the “I” is never connected to any one characteristic.

Or any one experience it’s having.

So it’s a substance, and the substance is not affected by anything external to it.

You can think about some of the philosophical theology of the ancient church. God is immutable, impassable. All of that comes out of substance thinking.

For Gautama to have recognized that, when we’re talking about this “I”, we’re not talking about anything, it was a remarkable achievement.

There is no I that carries “me” consistently through life.

It went against language; and to think in language ideas that flow against the same language you’re using to express them in is a real achievement.

Draw the connection for us, then, between substance thinking and sight.

The prominence of the noun is a product of sight.

I see what I assume to be substances that something is happening to. I see a dog – a substance in this case – getting rained on.

But of course, the product of sight is, in fact, just the visual phenomenon..

We don’t actually experience a substance. We just have visual phenomena that we, depending on our frame of reference, may interpret as a substance.

Do you have an example of a not so sight-oriented culture and how it affects our assumptions about reality?

I wouldn’t say Chinese necessarily, but it definitely puts an emphasis upon hearing. It puts an emphasis upon what happens.

The emphasis is less on what’s happening to a substance than on the happening itself.

So, it’s event-based rather than substance-based and points to what Gautama talks about.

That there is no substance underlying reality. There are sequences of events.

This is also true of Hebrew and of the Jewish Christian scriptures. They are hearing oriented.

In those traditions, the world is spoken into existence.

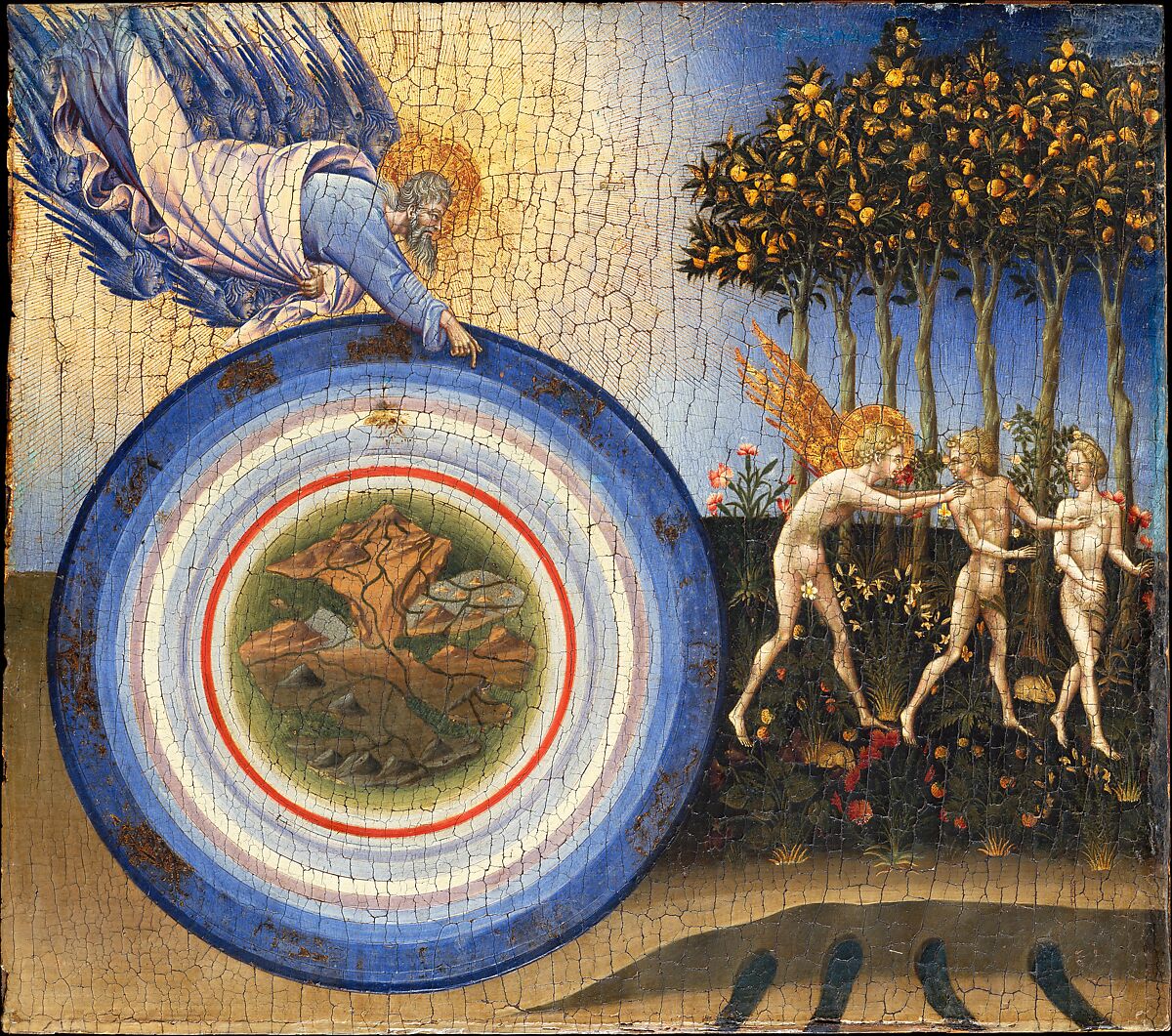

Attempting to visualize what’s going on in the first chapter of Genesis is extremely difficult. I don’t mean that they didn’t try to do it, but it’s very clear that what exists is what God calls it to be.

And in the New Testament – “In the beginning was the Word…”

If you have someone who’s blind from birth, it’s almost certain that sound will be the main medium of communication or of imagination.

Are you saying that if a person’s imagination is shaped by sound rather than by sight, the person might relate to the world in a different way?

When our sense of reality is shaped by hearing other people speaking to us, we don’t have to engage in some separate kind of inquiry to decide that there really are other people. And by other people, we mean other entities that are similar to ourselves.

Hearing gives us other subjects. Sight gives us a world of objects.

How is it that hearing tells us that reality is made up of other subjects rather than objects?

Well, you see, sounds exist in an inherently relational way. With sight, you can take an increasingly shorter period time but you still seem to see the same thing. With sound, if you cut it down far enough, it has no meaning whatsoever; it depends on existing within a context of other beings which also make sound.

You’re saying that if I’m looking at a dog standing in the rain, it looks like you’re seeing the same dog whether it’s for two seconds or one second or a split second or just a flash. Whereas if someone is telling you that a dog is standing in the rain, it matters a great deal whether or not you hear the whole of that sentence or phrase or you just hear blips of sound.

When you hear one syllable of a word, you hear a sound. But, what you actually hear primarily are words that have meaning. And, even the word is heard as a part of the sentence.

With hearing, context is everything – you can’t separate out a sound from its context and still be able to make sense of it. You take it all in.

So, we are explaining the whole in terms of multiple moments. You understand the moment in terms of the larger period of time.

To go back to our dog example, if your understanding of reality is more hearing-based, you can’t separate out “dog” from the larger context of what you’re hearing about the dog. There is no “dog” that rain is happening to, to continue our thought from before. The only dog that exists is the dog that at that moment is standing in the rain. The dog and the event are one. Separating out the dog from the event of the dog in the rain is an abstraction that a hearing-based interpretation of the world doesn’t necessarily lead to, because hearing is dependent on context to make any sense at all.

We really, if we abstract the sounds from the meanings that they could make…

Abstract a few odd sounds from the sequence of a story, let’s say.

Yes. We know we’re not talking about what actually happened.

It’s just a few utterances that make no sense. What is most real, then, to follow this logic, is not an abstracted substance pulled from an event, so to speak, but the events themselves. We don’t exist apart from the events we’re embedded in.

And this leads to stories as a major form of communication. And it leads to history.

The world of vision, however, makes a sharp distinction between the phenomena – what’s happening – and substances – the thing that other things are happening to. And so when people philosophically become skeptical about substances…

Whether there is a substantial there there, so the speak. Some thing that is the underlying substance that things happen to…

…they have only phenomena left – appearances.

But a world of appearances only is a deadend.

Appearances simply by themselves have no meaning.

The phenomena versus substance is a problem that arises for a visually oriented culture. It doesn’t arise for a hearing oriented culture.

Any experience we have of hearing is, by its nature, really very complex. And you can say the same thing with sight. But I guess we have more of a discriminatory ability with sight, in some ways.

Sight, I mean, to think that sight is not important, of course, would be nonsense. It’s interesting that, see, there are two basic ways in which people explain things.

If I ask you to explain why you’re feeling better, you can tell me a story.

That would be the hearing-oriented approach.

Or if you knew, if you knew the answer, you could describe to me what’s going on in your body. And what was going on in your body before and what is now going on in your body. That’s the scientific approach.

These chemical substances are interacting with these other chemicals…

But for many things, purposes and ordinary life, we think telling stories is the easier way of explaining things. And in many ways, the more meaningful.

Stories really give you better guidance than the detailed scientific account of what was happening to the nerves in your brain, how that was transmitted to other parts of the body, and so forth. But they should be complementary to each other. And I think in much of the West, they have been complementary.

That is, both sight and sound. The scientific method and stories.

And I think that the lead of the West in developing a science of explanation being forced upon every other way has depended upon there also being another kind of explanation.

Reality understood by sight alone won’t give you the same picture as a reality that’s also informed by sound. Sight needs sound. Science needs story.

But the scientists do not generalize. There is a tendency for people who have immersed themselves in the science that, when they’re told a story, to think that’s not an explanation.

And therefore the humanities, which are more likely to be about stories, are being increasingly marginalized in higher education.

History, when it’s allowed to be real history, is always most interested in the uniqueness of events.

Science is more interested in repeating events.

So, a sight-based vision of the world, you’d say, leads more to thinking about substances as the ultimate reality and because they persist through time with events happening to them, rather than being in change themselves. But a hearing-based vision, where events are most fundamental, leads to stories – which never repeat exactly but are always unique.

And I think that interest in uniqueness is probably not universal.

All this is fascinating, but how is it important to the moment we’re living in now? How does it relate to the crises we face?

I think historical consciousness opens people to think about the future as being very different from the past.

Because the events of history never exactly repeat. The future is always open.

Scientific thinking may come out with predictions of that kind. And obviously, scientists have been among those who were telling us that the future was going to be very different. But I think that it’s people with historical consciousness who really existentially appropriate that.

Feel it in their bones.

It’s also because science as such does not give any indication that we should do anything.

Do anything about what we see happening in the world.

It’s purely objectifying. And if we don’t have a fundamentally value-oriented view of reality…You see, that’s why meaninglessness is so important. If you think scientifically, you just think that purpose has played no role. So having a purpose, like preventing these things from happening, is not really given status.

In a purely scientific model.

So if you believe they’re happening…

Climate change and biodiversity loss, etc., etc.

… you can be an observer.

But I do think that it’s important that people feel some responsibility for what happens. And you don’t really get that out of the scientific worldview.

That doesn’t mean that no scientist has that. But the tendency of the community of scientists has not pushed them in that direction. But there are so many wonderful exceptions.

And so I think when they try to do value-free teaching, which means simply presenting facts as facts, a student who has an historical orientation…

More story-based, more hearing-based, and more event- rather than substance-based…

…thinks values are important, thinks it’s important that there be a living planet, can use that information, subsume it within the historical, ethical, moral, interpersonal vision, and do wonderful things.