What is a Pando Days project?

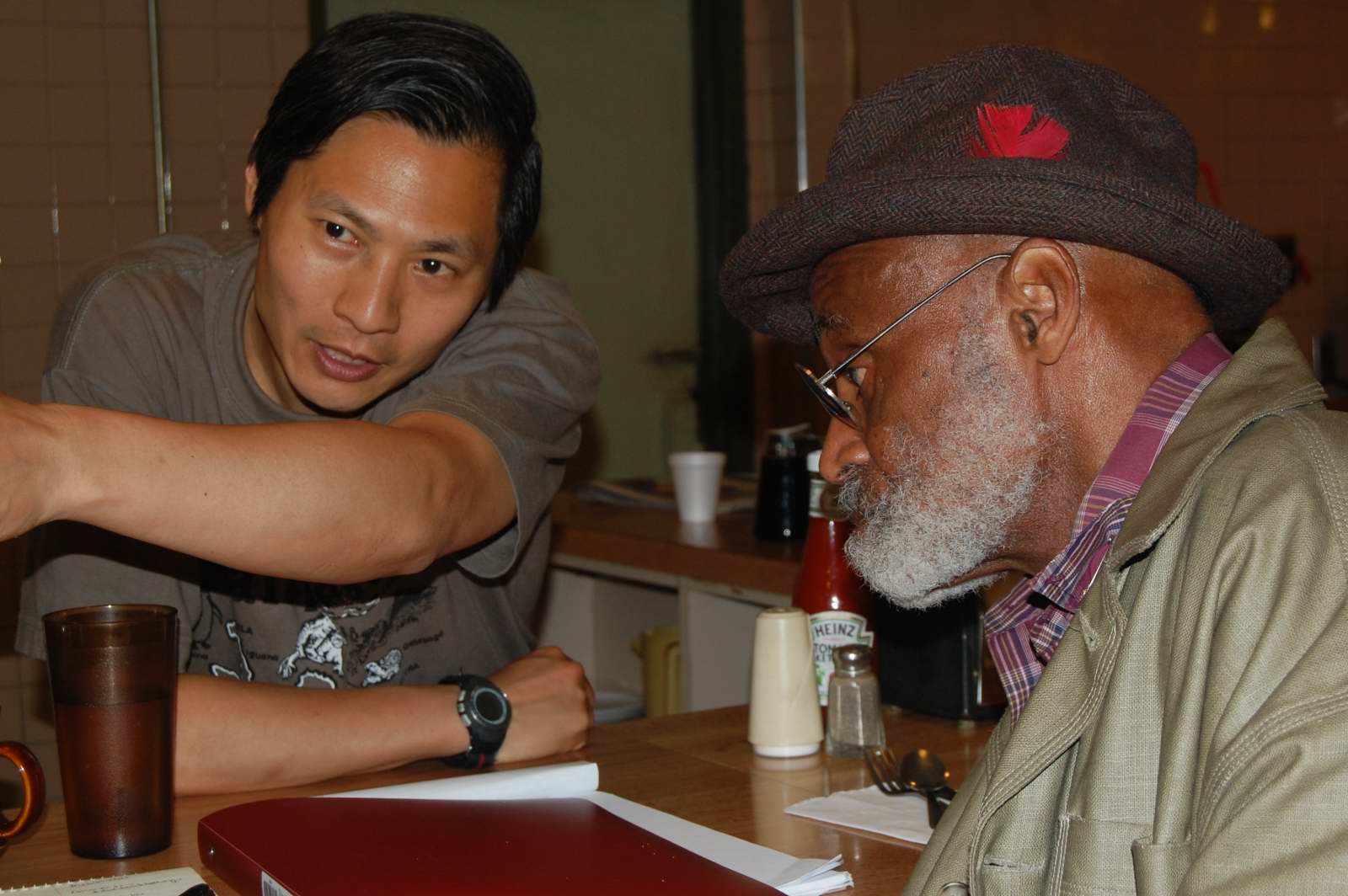

Doug Chang is Series Producer of Pando Days. We sat down with him to talk about what exactly is a Pando Days project.

PANDO: Doug, wonderful to be working with you! As Pando Days Series Producer, you’ve had a chance to dive in and discuss projects under development this fall with all the participating colleges and universities. So, let’s wind back and start at the beginning: What is a Pando Days project?

DOUG: One of the things I love about the Pando Days approach is that it gives higher education programs incentive to step outside academia – to transform research and learning into actual projects with concrete goals, results and ramifications. And, to think of these projects as models for further investigation.

In a very short time (really over the course of one semester), teams of students and educators are being asked to devise a course of collective action that produces, at the end of the term, a clear and concrete set of deliverables.

But the projects don’t end there. Often they are just laying the groundwork for future initiatives that will continue under the watch of instructors with other students, partnering organizations or community groups.

There are various approaches to project-based learning. What do you think is unique about Pando Days?

First, it’s Pando’s focus on the LA County sustainability plan – OurCounty LA – which is broadly defined. I hear it has been called the most ambitious regional plan in the country – for exactly this reason. It invites holistic thinking from corners of the educational spectrum that aren’t typically included in a more limited sustainability focus.

Then, Pando Days is not just about project- or challenge-based courses – however wonderful they are. It’s about developing out of the coursework real-world projects that can get implemented and given a test-drive.

We call them small bets.

The specificity of these projects and their direct impact on actual sites throughout Los Angeles County gives them a real urgency and dynamism – we begin to appreciate how even wildly ambitious goals can be incrementally achieved over time. This is something I would like to see replicated in other regions around the country – and I think programs like Pando Days will eventually make that happen.

We also talk about them being transdisciplinary – not just interdisciplinary, but addressing the whole of lived experience. And we hope they stimulate intellectual thought.

I’ve heard you ask, “If sustainability is the goal, what are we saying is really worth sustaining?” Pando Day Projects explore just these sorts of questions, interweaving science and engineering with economics, environmental justice, social studies, philosophy, psychology, the arts, even religion and always ethics, placing heavy emphasis on the experience of being and belonging in a specific lived environment.

Several of the instructors I’ve spoken with have highlighted what you call the transdisciplinary nature of their work. I’d like to believe this leads to more unified support for coordinated, effective and long-term transformations.

This is your first year to be involved with Pando Days, but you’ve read through the projects from the past. Do you have any favorites?

I’d hate to name one. Each of the projects has something exciting or innovative to offer, and all of them are so different, both in scope and application. Some can lead to concrete results very quickly – you can almost imagine them happening as we speak. Others take a more abstract, “visionary” approach that may require years or even decades to be realized.

Any of them particularly speak to you?

Ok, I’ll call out two. Woodbury’s Mobile Cooling Rooms project finds modern applications for age-old natural cooling techniques (presumably arrived at through painstaking trial and error over the course of centuries), employing 21st Century artistic and scientific methods to refine their use and design. I mean, that’s pretty amazing just in terms of content. And the potential for ongoing creative experiment, combining measurable effects with qualities touching the human spirit and emotions, was amply demonstrated in the clay-based prototypes presented.

And then the Cal State Long Beach team proposed a remarkably simple approach to the problems of congestion in the hyper-populated city of Cudahy, weaving together a system of available technology and community-based governance to amplify the impact of both.

You have a background in nurturing a broad range of arts and culture television programming, including non-fiction. How does this help in terms of curating the Pando Days projects now?

The consistent theme running through my work, whether it’s in documentary, narrative film, theater or performance, has been the desire to reach a truer, more nuanced understanding of the world not through polemics but through process.

My own projects always start from a vague, persuasive notion which I then proceed to explore and refine through the making of the project itself. Often the net result turns out differently, and sometimes better, than I initially imagine. I learn things along the way. This is how I hope students will approach their Pando Days Projects.

What do you see as the role of storytelling in the projects?

The projects themselves give students concrete, hands-on experience in community-based research and development that will (hopefully) shape the future. You can’t describe what the future can be like without telling some kind of story. Nothing gives you a more persuasive sense of how ideas become real.