Interview with Tucker Nichols

Tucker Nichols, artist-in-residence for the 2015 Pando Populus conference, sat down with Kevin Madden, managing editor for the Pando Populus blog, to discuss his art and life and the relationship of both to the Earth.

Tucker, tell us about your background as an artist. What do you do?

Tucker Nichols: I’m based in San Rafael, California. I’m an artist who tends to work outside of the typical boundaries of what that means. I do plenty of paintings and drawings, and I show things in galleries and museums. But I like to bring the way I think about art to other places as well. I draw on walls. I make books. I make drawings for the New York Times op-ed pages.

One of the things that I also do is strategy work—draw in meetings. I’ve been working with John Bielenberg and Greg Galle at Future for about ten years now. I mostly do editorial drawings around what people are talking about in various workshops—what they call blitzes.

What I really like about being an artist is that it’s a way for me to think about things that I haven’t thought about yet. It’s one thing to do that in your studio, but it’s another thing to take that process to the bigger, vexing problems of the world to see what happens.

When you were presented with Pando Populus, what sort of thoughts led you to the artwork you developed for the group?

Like any of us today, I am fascinated, repelled, and terrified by climate change and what that will mean for life on earth as we know it. At the same time, I’m really tired of what that has come to look like. The notion of saving the earth does not really mean anything to me; I’m not sure what I’m supposed to think when I keep seeing that. So I started thinking about how else we might think about saving everything, and what it means to be thinking about this problem from a slightly different perspective as Pando is doing. The drawings come out of my own frustration with the rhetoric of saving the earth, and also my own fascination and fears around the problems coming down the road.

Tell us about some of the drawings you developed with Pando Populus.

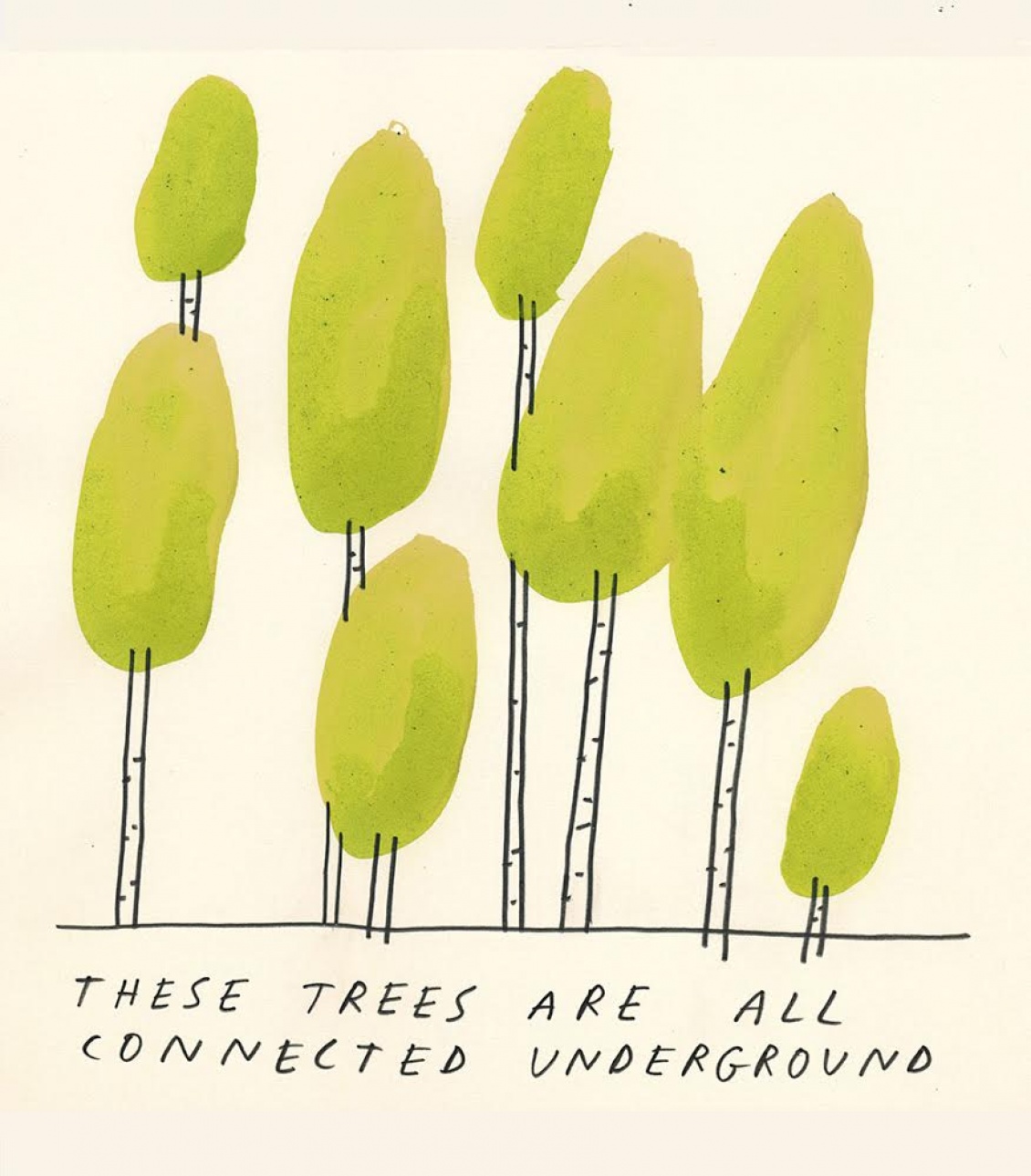

The aspen grove came out from us trying to visualize this idea of us trying to see our lives as separate, when actually we are all totally connected. This one single organism, which is apparently the largest living thing on earth, has all its roots connected underground. We all gravitated toward that idea. Once we started talking about that, we realized it was a great way to start synthesizing an idea around how to think of ourselves as we go forward through dangerous times. I connected their roots more like tangled cords than a root system because that’s what connection really feels like to me. It’s messy and intertwined.

You also came up with a drawing that sort of looks like two connected sock puppets talking to each other. Could you tell us a bit about that one too?

I think when I first made that one it had a phrase underneath, something like “we’re all in this together.” We have an idea that we are each autonomous, unique forces. It seemed that one way to speak to that assumption was through a two-headed monster that couldn’t get away from itself if it wanted to. I think we have an idea of ourselves as being separate entities that need to defend our turf and get as many resources as we can grab. A two-headed monster isn’t going to do well if it’s trying to keep the other head from eating.

Part of what Pando Populus has really embraced is the fostering of an ecological civilization, changing how we live with the natural world. When confronted with something as large and abstract as climate change and our changing ecology, how can visual art help us change our way of thinking and break out of an older pattern?

I think art has emerged for humans as a way to express things that we don’t know how to say, either because they are too abstract or too emotionally intense, or we just don’t have words for them. So for something as broad, scary, and abstract as climate change, art is a good tool to get at some of those feelings. Generally, art can be very good at touching on things we don’t know how to say. But it’s very bad at being specific, unless maybe it’s political art. For me it’s almost like typing with mittens on—you can’t exactly say what you’re trying to get across, but you can express a vague feeling that you can’t necessarily express in words.

So for me, art has dropped into a great slot of expression to take on the things I don’t know quite how to talk about.

Could you talk about your personal connection to climate change and the environment?

It occurred to me when I was first working on the Pando stuff that going forward it will be impossible to work on anything that is not somehow connected to climate change. It’s such a big problem for us all, we’ll no longer be able to have environmental studies departments at universities, or people interested in the environment. We’re all going to be surviving in some way. Now hopefully that’s not going to look like some horrible apocalyptic vision, but we’re all going to be connected in some way if we aren’t already. Now increasingly every project I am working on is somehow tied back to living on earth, the future, and how we are doing that. I think as that realization starts to dawn on more people—that this isn’t an issue, but the issue—I think we’ll see really different ways of tackling it. I’m looking forward to getting away from some of the language we’ve seen for decades now that comes more from the environmental movement and really towards something that’s more like people just living on earth.