The EPA, US and Me

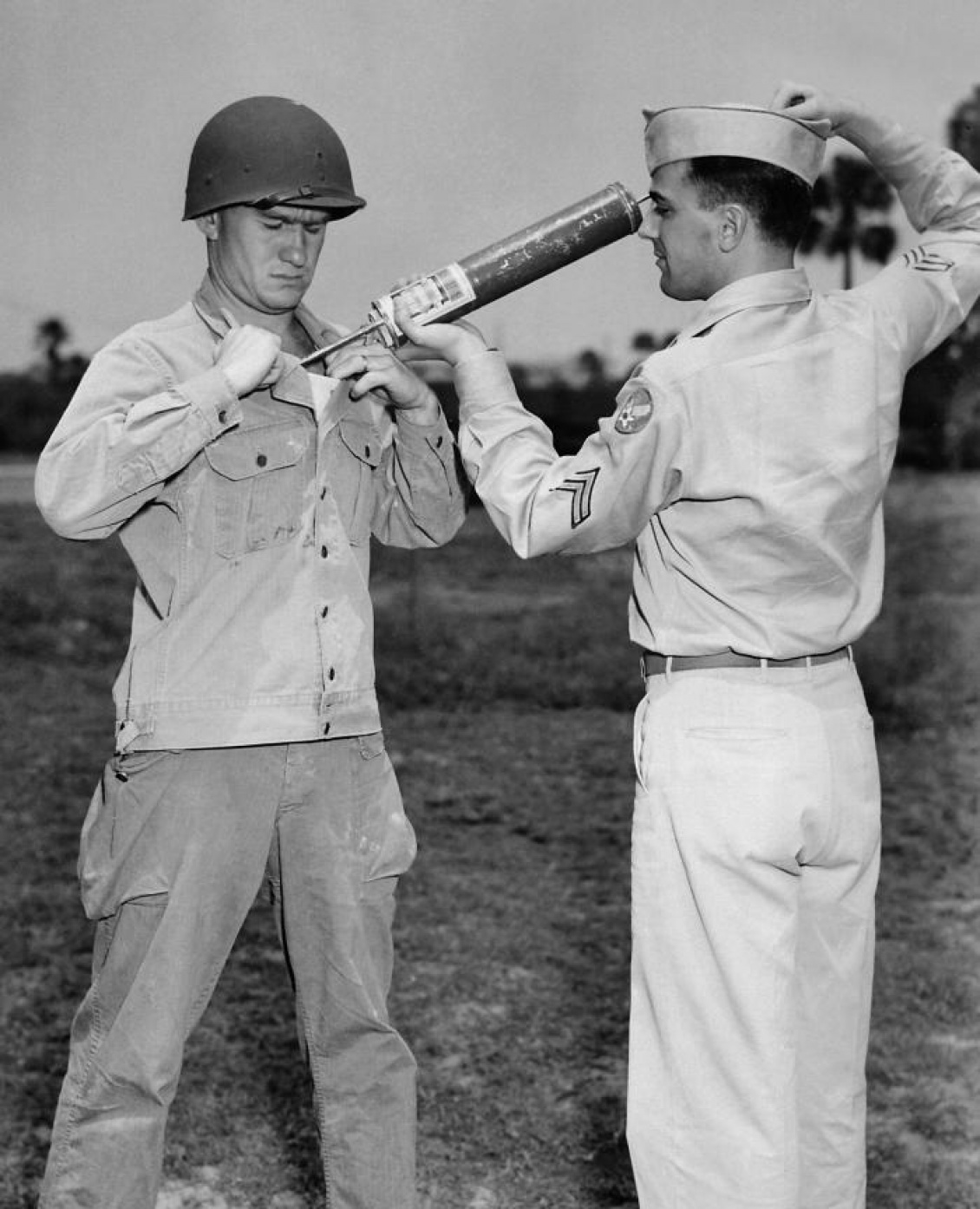

A U.S. soldier demonstrates DDT hand-spraying equipment (DDT was used to control the spread of lice).

By Evaggelos Vallianatos

I worked for the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) from the last two years of the Jimmy Carter administration to the end of the first administration of George W. Bush. This was a long time, twenty-five years.

I went to the EPA full of enthusiasm to make some difference to such a virtuous national enterprise: protecting the health of both humans and the natural world from countless invisible dangers.

After all, industrialized America was the Goliath of industrialized countries: blowing apart mountains for coal, fighting endless wars for petroleum, and allowing its agribusiness and chemical industries to alter the face of rural America by forcibly planting large-scale agriculture in the land of millions of family farmers.

This invisible upheaval and its deadly pollution became real to me in 1979 when I started my career at the EPA.

The EPA inside out

First of all, my colleagues told me the story of criminal laboratories faking data so that pesticide companies would have no trouble in getting EPA permission to bring their new creations to farmers. The EPA shut down several of those criminal labs but did nothing else to end that deadly practice.

Second, the EPA allowed products registered on the basis of fraud to remain on the market, and, therefore, in our food and drinking water.

Not only that, but the EPA reinvented itself and began seeing the world through the eyes of polluters. The choice was stark: change or die. The Reagan administration would not have the EPA keep “discovering” ever more criminal labs, as these discoveries always raised the question of what to do with the chemical industry, the greatest beneficiary of this criminal corruption.

In the 1980s, the EPA quietly outsourced its own responsibility of examining the data of the chemical companies.

Digging deeper

I, too, “discovered” lots of other things that brought me to dig further beneath the placid and boring face of the EPA: for example, spraying neurotoxins over crops ready to be harvested, which was not kind to farm workers. The EPA’s own studies in the late 1970s uncovered young farm workers that had the medical maladies associated with men some twenty-five years of age older.

Another EPA study, in the late 1970s, discovered tetra-dioxin, the deadliest of the dioxins, in a creek near the homes of women in Oregon who had reported an abnormal number of miscarriages. Timber companies and the U.S. Forest Service used to spray the neighboring forest of these women with the Agent Orange chemicals 2,4-D and 2,4,5-T. Both of these “weed killers,” so infamously used in the Vietnam War, were contaminated by tetra-dioxin. The discovery of the human effects of the dioxin contaminant helped the EPA in banning 2,4,5-T in 1983.

In the early 1980s, two of my EPA colleagues, David Coppage and Clayton Bushong, estimated the ecological and economic costs of using pesticides in the United States. They painted a picture of destruction and death all across America.

A single pesticide application or runoff, for example, might kill as many as a million fish. Coppage and Bushong cited a 1978 EPA study showing that pesticide pollution could cause acute kills of more than 100,000,000 fish a year. Spraying millions of acres of salt marsh and tidelands for mosquitoes would probably kill, every year, “billions of fish and aquatic invertebrates.” Fish-eating birds would also suffer tremendously, and likely fail to reproduce adequately.

Finally, Coppage and Bushong reported that DDT-like compounds, dieldrin and heptachlor, killed about eighty percent of songbirds, and “eliminated some game birds” (see David L. Coppage and Clayton Bushong, “On the Value of Wild Biotic Resources of the United States Affected by Pesticides,” Office of Pesticide Programs, U.S. EPA, [early 1980s]).

The EPA banned DDT and several other DDT-like compounds. But, like in the above case of criminal labs, political influence from the polluters and their allies in the White House and Congress deformed the EPA, blinding it to the real dangers of pollution and corruption.

A new EPA with real protection authority

We need to reinvent an independent EPA away from the deleterious effects of big money. A Supreme Court-like EPA can tackle both environmental crimes and environmental protection.

Part of such a dream should include an independent national laboratory and bring the chemical industry under the law. No company would have the right to “test” its own products. And there should be severe penalties against those lobbying the EPA.

We need an independent EPA just like we need plenty of oxygen. Time has come to put our health and the health of the natural world at the top of our priorities. Nothing is more important.

Evaggelos Vallianatos is the author of several books, including the most recent, Poison Spring (with McKay Jenkins, Bloomsbury Press), published April 8, 2014. He will be making a presentation on Poison Spring on Tuesday, September 1, at 11:30 a.m. at the University Club of Claremont, in Claremont, CA.