The Emerald Necklace

Editor’s note: John Cobb, Jr. prepared these comments for the inaugural docent training program of the Amigos de los Rios Emerald Necklace initiative, a “necklace” of parks and green spaces populating the great watersheds of the Los Angeles region about which docents will be trained. The docent training program is developed in collaboration with Pando Hubs.

I grew up thinking that being civilized was an entirely good thing, and I am certainly a product of urban—that is, civilized—life. But a few decades ago I met a man, Paul Shepard, who thought that civilized life is bad. He wrote a book entitled, “Nature and Madness.” “Madness” is civilization. His account of the destructiveness, the social injustices, and the mutual slaughter that civilization brought into the world is largely convincing. In the end, however, my view has come to be that, like so many things, civilization has good features and bad features. Sadly, the bad features have led us to the brink of catastrophe. But we are stuck with civilization anyway, and I cannot imagine living without many of the good features. We may be able to get rid of some of the bad features and replace them with some of the good features of pre-civilized life. That might even lead us to save the habitability of this planet by bringing into being an ecological civilization.

Human vs. nature

The worst feature of civilizations, at least the feature most responsible for our making such a mess of things, is our alienation from nature. Before civilization, people lived in and with the rest of nature. Of course, they had some artificial things: instruments and weapons, for example. Many of them lived in villages, and their homes were certainly humanly created. Nevertheless, the natural world dominated their horizons and their imaginations. Basically they adjusted their lives to nature rather that reshaping nature for their convenience.

But when they built large cities, this changed. Many people still lived close to the earth, but often they were slaves of urban dwellers, doing specialized work and imposing the will of their masters on the land. Meanwhile the city dwellers were surrounded by human creations. They became somewhat independent of weather. They began to communicate in written language. Trade replaced farming for many of them. Nature was the source of their wealth, but it was something to be acquired and used rather than their home.

This was just the first stage in the process of alienation. We moderns have carried it much further and are the most alienated people who have ever lived. Whereas until recently most people were involved in farming, now most of us grow up thinking of food as something bought in the grocery store. We have very little idea what the plants looked like when they were growing. We are much more familiar with pork, ham, and bacon than with pigs.

Many of us have pets that connect us to a few animal species in a positive way, but in our imagination these are totally different from the animals we eat. If we are lucky we may experience growing something in a garden. But many of us are not that lucky. And if we are, this is an exotic pastime that has nothing to do with our basic activities and interests. We hardly know what grains are like. We are aware vaguely that there are huge machines that collect and process what grows in the field. The connection between grain and the bread we eat is a complete mystery.

If someone asks where I live, I give them a street address and the name of my city. If I add anything it is the ZIP. It doesn’t occur to me to locate myself in terms of mountains, boulders, meadows, forests, and streams.

I finally learned that, in order to be respectful to the people from whom we stole this land, I should learn who they are and ask them to welcome us when we have large meetings. Through recognizing them, we indirectly acknowledge the natural world that was their home. Otherwise, the mountains are there for viewing and hiking and the water is artificially directed and stored for efficient use.

I am not saying that everyone is as alienated as I am. I hope you are not. But I fear that I am all too representative of a large section of the population. And our collective behavior, for example, the ignoring of the crisis of nature by our politicians in the current election cycle, suggests that many are even more alienated than it.

Modernity and alienation

I was shocked into recognizing the consequences of the general alienation of Euro-Americans in the 1960s. Since then I have been trying to see the consequences that have followed from it and, at least, to stop contributing so much to those consequences. Truly overcoming the alienation is far more difficult.

For us alienated moderns, nature is property to be bought and sold. Its “value” is its price. Great fortunes are acquired as property prices rise. Sometimes a collapse of land prices causes a major recession. The value of land is a matter of its location rather than its natural properties.

This practical objectification of nature went along with the development of philosophical ideas. In the Middle Ages, the objectification had not gone quite as far. A widespread idea was that there is a great chain of being extending from the lowest to the highest levels. Merely material things might be the lowest level. Living things were certainly superior to merely material ones, and there were many grades of these. Plants came first. Perhaps insects came next, then fish, then birds, then reptiles, then mammals, and human beings. The chain did not end there. Above human beings there were angels, perhaps several grades of them. And above all that, at the pinnacle, was God. Of course, I have not been exhaustive of the medieval hierarchy, and today we would have to list much more. My point is only to give an impression of multiple levels with some connectedness.

Human beings were certainly regarded as different from and superior to other animals, just as the animals were regarded as different from and superior to plants. But the gap between humans and other mammals might be less than that between these other mammals and insects. One may criticize this great chain of being idea, but it did not drastically alienate human beings from the rest of nature. Humans thought of themselves as the apex of this world, but below other, more fully spiritual, creatures. And very far below God.

A completely alienated view was taken seriously only in modern times. The “father” of modern philosophy and modern science was Rene Descartes. He flourished around the middle of the seventeenth century. He wanted to develop a simpler and sharply delineated scheme that would liberate scientists from any moral restrictions on how they treated natural things. He proposed that there are only two kinds of things: mind and matter. Living things (except for humans) are to be explained entirely in terms of matter.

This idea seems contrary to common thinking even today, even after our most respected leaders, our scientists, have taught it for centuries. Very few people really believe that their pet dog, for instance, is just a complex organization of matter. But Descartes was serious in proposing just that. He thought that matter could be arranged into complex machines that could act as though they were alive. The supporters of this mechanical model of animals often appealed, in those days, to the clock on the cathedral of Strasbourg. Every hour, human-like figures came out and danced around for the enjoyment of observers. The point is that machines can move in ways that look life-like to us. While Descartes was quite sure that we humans are not machines, he taught that all other living things are.

I think you will agree that this is a thoroughly alienated and alienating view. It means, for example, that dogs have no feelings of enjoyment or pain. They simply act as if they did. Descartes’ followers at times treated animals very cruelly with no regard to their feelings because they were persuaded that there were no such feelings.

Before you decide that this is irrelevant to our time, think of the industrial production of meat. In this process, cows, pigs, and chickens are not treated as individual beings with their own experiences. In this industrial context, the feelings of the animals play no role. Decisions are made in terms of the maximization of profit. The suffering of animals matters only if it affects the boom line of the industry.

Theoretically, Descartes’ understanding of nature has won the day in modern science. A scientific explanation can never include the feelings, purposes, or decisions of the entities that are studied, even if these are animals that are close kin to us Animals are explained in the same way as machines, although, of course, with much greater complexity.

Since Darwin demonstrated that we humans are part of nature, the same approach is being taken in the scientific study of us. What had distinguished us most sharply from other animals in Descartes’ view is that we think. But now we can make machines that think; indeed, in some ways they think much better than we do. From the point of view of modern science, we human beings are also machines and part of the great cosmic machine.

No doubt this radically alienated view of modern science reflects the alienation inherent in civilization. But the theoretical reduction of nature, now including us as well, to mechanisms has certainly added to, and rigidified, the alienation. I am glad to say that although this materialist view remains standard science, its limitations, even for science, are becoming clearer and clearer. Quantum phenomena cannot be explained in these categories. Even plants appear to have nonmechanical functions, and the mechanistic model has never worked well in the explanation of animal behavior. The effort to explain us human beings in purely mechanistic terms encounters evidence that our thought and mental practices have an effect on our brains. Few people really believe that they are zombies, but the mechanistic model still shapes much of our collective behavior.

An alternative view of the natural world (and ourselves)

There is an alternative: We can think of the world as made up of organisms rather than mechanisms. Although this alternative has by no means won the battle in the university, I strongly recommend that we look at nature in that way. All that has been learned with the mechanical model can be retained, and features of reality that do not fit that model can be understood as well. We can understand ourselves much better as organisms in a world of organisms.

One difference between organisms and mechanisms is that organisms are always and necessarily interacting with their environments. If an organism moves from one environment to another, it changes. Think of the difference between your experience now and when you are at home. Thus an organism is always interacting with other organisms. It is never self-contained.

We, as organisms, are at home in a world of other organisms. We are affected by them. They are affected by us. With this model we can, at least in thought, break out of the extreme alienation to which the mechanical model has so greatly contributed.

What have been the consequences of this alienation? Over millennia it has led to loss of plant cover and of soil, and thus to desertification. Ancient civilizations came to end when they had exhausted the capacity of the land to support them. But only in the modern world is this taking place on a scale and at a rate that portends global catastrophe.

Deforestation has changed landscapes from ancient times. But today it is not only causing massive erosion, destruction of watersheds, and flooding. It is also contributing to climate change. It is responsible for the extinction of thousands of species of living things. How that will change the biosphere we do not know. All this destruction results from our viewing nature as a resource for urban living and ever-increasing consumption. It could not happen if we saw it as our home or mother.

It is almost impossible for urban people actually to recover the unalienated sensibility of those who lived within nature as part of the natural world. A few deep ecologists affirm judgments that might reflect that alternative experience of nature. They are to be admired, but their achievements cannot seriously be held up as the goal for all. Most of us are condemned to live in artificial environments whose construction and maintenance is inherently exploitative of nature.

But our consciousness can be raised. We can become aware of what we are doing to the natural world. We can seek to reduce the damage by changing our own lifestyles. We can support all those who find ways not only quantitatively to reduce the damage but also to develop greater efficiency, and then, technology that avoids using what is most damaging. We could talk for a long time about how we urban people can reduce our ecological footprint, and that is very important. But today we are looking in a different direction.

We can recover some of the understanding of ourselves as living in a natural context. It turns out that even the most alienated of us enjoy “nature.” That enjoyment, I think, is not just superficial aesthetics or fun. It is something much deeper than that. We can find ourselves reconnected to our original environment.

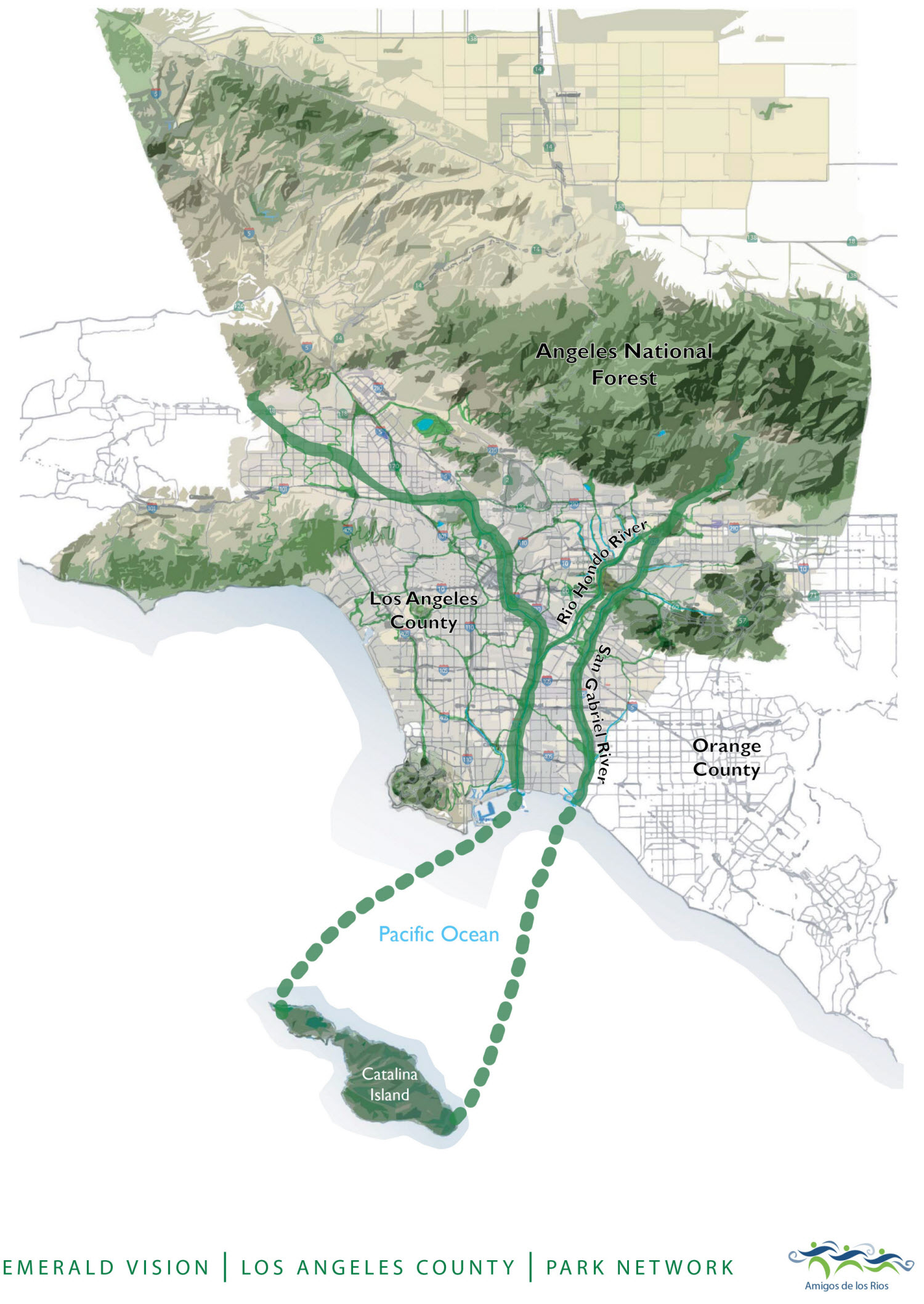

Southern California’s Emerald Necklace

We are proud and grateful for the success of the long drawn out struggle to save the naturalness of our local mountains. The establishment of the new San Gabriel Mountains National Monument gives us all a nearby area in which we can get away from our usual artificial environment. It will at least check the tendency to view this land only as a source of profits for the few. It will be available to all. And much of it will retain some genuine naturalness.

Today we are celebrating another initiative—to teach people about the “Emerald Necklace.” We cannot fully recover the sense that our real environment is nature, but as urban, civilized people, we can learn about the natural world in which we still live. We can be taught to observe its important features and to appreciate the ways they still shape our lives. We can learn about native fauna and flora. We can trace what happens to water. We can observe the consequences of drought. We can study the history and the stages of deterioration of the land, and also the possibilities of restoration. Above all, we can discover that despite all the destruction we have inflicted on our natural environment, there is still much to enjoy, much to wonder at, much that remains mysterious.

There may be quite practical advantages as more citizens understand their natural context better. From time to time there are proposals to construct something or demolish something or move something. The change may threaten or benefit the watershed. Most of us understand such things too little to participate wisely in these discussions. Sadly the one who spends the most money promoting one side of the argument is likely to win our votes. Often that means that nature, as well as all of us who ignorantly depend on it, lose. We do not need always to remain quite so ignorant. If tens of thousands of us are informed, hundreds of thousands will vote more wisely.

You who plan to give generously of your time as docents may feel that I am putting a heavy burden on your shoulders. I hope not. You don’t need to teach people about the inherent problems of civilization or tell them that as products of civilization they are all alienated from nature. You do not need to teach them the history of thought or the harm done by the mechanistic model of modernity. You do not need to persuade them that the organic model works better.

You just need to teach them the truth about the natural world in which we live and how much is to be gained from understanding it, appreciating it, and experiencing it. You need to communicate the danger of humans continuing to exploit it for the profit of the few.

But I would like for you to understand that as you do your job as docents, you are doing more than just sharing information with a few people. You are contributing to improving the chances that the human species will survive and flourish. We will do so only if we appreciate how deeply our health and our destiny are bound up with that of the natural world. You can show people how human life is interconnected with the natural world in concrete ways that matter to all.